When I was in elementary school, I was lucky enough to have a teacher named Mrs. Bayles who believed that what it meant to be “cool” was enjoy solving really interesting problems. I remember one time she gave everyone in class a piece of pie and asked us all “What’s the best way to start eating this piece of pie?” and everyone else in the classroom immediately took their fork and stabbed it right in that pointy corner, where, they argued, they would get the most of the juicy center of whatever type of pie they  had. I was sitting with my group of friends (mostly girls) who were self-defined math “geeks” (although I think back in 1976, that’s not what they were called). We all kept thinking about that and eventually came to the conclusion that we wanted to start with the crust because thought saving the middle for last was a great idea.

had. I was sitting with my group of friends (mostly girls) who were self-defined math “geeks” (although I think back in 1976, that’s not what they were called). We all kept thinking about that and eventually came to the conclusion that we wanted to start with the crust because thought saving the middle for last was a great idea.

Mrs. Bayles thought that was so awesome and asked the four us to come up to the front of the room, draw a diagram on the board and give evidence as to why eating pie from the back of the piece of pie was somehow better than eating it from the tip. We thought we were the Albert Einsteins of pie-eating. We just loved it. Even though the other kids in the class thought it was kind of weird, since we could justify our choice with a good argument, we stood together and most importantly, Mrs. Bayles respected our evidence and let us have our authority in our say.

One of the things in recent years that has become a passion of mine in the mathematics classroom, and more precisely, the mathematics probem-based learning classroom, is the idea of status and positioning of students in the discourse and learning that occurs. This has become such an important issue that I invited one of our keynote speakers this year at the PBL Math Teaching Summit to speak on this very subject. After many, many years of hearing teachers’ concerns about how to handle a student who tends to dominate a conversation, or who doesn’t speak enough, or what happens when kids get off on the wrong the track when discussing a problem – it is about time that this socio-emotional topic (which includes race, gender, privilege, equity, and all things relational that made me start studying this pedagogy in the first place years ago) be moved to forefront of the mathematics classroom once and for all. (Aside – huge thank you to Teresa Dunleavy who gave an awesome talk on this BTW!)

I have shared this specific story with so many people at this point in time, but I find it so important that I want to repeat it here for Sam Shah’s “How does your class move the needle on what your kids think about …. who can do math?” prompt for this “Virtual Conference on Mathematical Flavors.” I feel it is something I’ve worked on for almost twenty or so years and I still don’t have it down to a science, I just know that I can’t let it go anymore.

In my classroom, I allow students to use dynamic geometry apps or technology as much as they want to justify their answers or as evidence for their thinking, as long as it doesn’t go awry (and of course, as long as it is correct and they can describe their thinking). Two years ago, I had a student (for whom I will use a pseudonym here because I’ve used his real name in the story, but not on the Internet), I’ll call Ernie. Ernie was one of those kids who could do no wrong – very popular in his current class, very successful academically, which made him very outspoken in his ideas, very good-looking in our white, hetero-normative, social class acceptable way and to top it off – (what Dr. Dunleavy says is usually one of the highest privileges in white schooling) – an exceptional athlete. Mix all of these privileges together and what automatically came with him into this class? Mathematical status.

Mathematical status doesn’t mean that he was not a good math student, that’s for sure. Ernie worked very hard and had excellent intuition, as well as good retention from his past math courses (–hmm, I feel like I’m writing comments from the fall term here..) These were neither here nor there however to the rest of the class. When students bring their own thoughts and impressions of a student into the class with them, its the class itself that priveleges that other student (in this case Ernie) the high mathematical status that he had. There might have been other students in the class who should have had higher status but because they were not as outspoken, had different relationships with others, were messy or not as articulate about their ideas, asked “stupid” questions (you know that’s not what I mean) or whatever the behavior that was exhibited – the other students in the class would assign a low mathematical status to other students by the things they say, brushing aside questions or simply by just not listening.

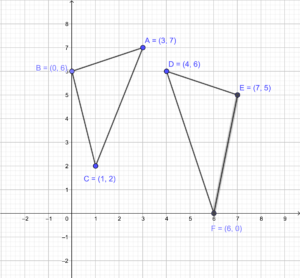

So one day we were discussing a question about the congruence of two triangles that were in the different orientation, plotted with coordinates. Students were supposed to come up with some triangle congruence criteria (I believe it was supposed to be SSS) for why the two triangles were congruent – this was at the very beginning of the concept of Triangle Congruence. Ernie had plotted the triangles on GeoGebra and simply said, “These two triangles are not congruent because all of the correponding sides  are not equal” stepped back, matter-of-factly with pride in a job well done.

are not equal” stepped back, matter-of-factly with pride in a job well done.

There was thoughtful silence in the room as the class looked at this diagram up on the board projected from his laptop. There was no arguing with the fact that the sides of his triangles were not all the same. However, there was still confusion I could see in some of the students’ faces. Some kids asked him to find the lengths of the sides. “That’s what I got,” “Oh I see what I did wrong,” and “Thanks for clarifying” were some of the comments that Ernie received. Under her breath, I heard one girl just whipsering to herself, “That doesn’t make sense” and I tried to follow up on the comment, but she would have none of it. We spent maybe 5 more minutes of me trying to get anyone else to make a comment. It got to the point where I even got out my solutions because even I was doubting myself (the power of Ernie’s status) because I had sworn that those two triangles were supposed to come out congruent. I knew some of those kids knew it too. Why weren’t they all saying something? It was as simple as a misplaced point. Not a huge problem, why couldn’t anyone call him on it? I decided to do a little experiment. “OK, well let’s move on then, but I really think there’s a way to show that these two triangles are congruent.” Ernie was intrigued. He couldn’t be wrong so tried to start finding his error, but couldn’t. I said, “no, no, I want everyone to go home tonight and try to see if we can find a way to show that these triangles are congruent.”

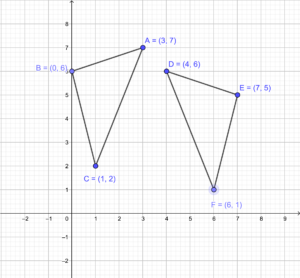

Jump to the next day in class and kids are sharing their solutions from the previous nights struggle problems. Before we start discussing them, I say, “Did anyone think about the problem that Ernie presented yesterday?” Radio silence….I wasn’t sure that anyone would actually do it, so I had come prepared with a geogebra diagram of my own. I projected it on the whiteboard and asked if they noticed anything. Still no one said anything (outloud so everyone could hear, but I could tell that some students were at least talking to each other). Suddenly, Ernie says, “Oh my gosh, I plotted the wrong point! It was supposed to be (6,1).” There was this huge metaphorical sigh of relief from the whole class at this moment that could be felt by everyone. I just coudn’t understand it. Although no one was willing to speak up that they knew Ernie had been wrong, they were all relieved that that he realized his own error.

each other). Suddenly, Ernie says, “Oh my gosh, I plotted the wrong point! It was supposed to be (6,1).” There was this huge metaphorical sigh of relief from the whole class at this moment that could be felt by everyone. I just coudn’t understand it. Although no one was willing to speak up that they knew Ernie had been wrong, they were all relieved that that he realized his own error.

I expressed my concern with this dynamic in my classroom. Simply asking them why didn’t anyone help Ernie with the problem yesterday in class? or what kept anyone from speaking up when they thought the triangles were congruent? wasn’t getting us anywhere. So what I did was tried to let them know how much I wanted to hear their ideas – similar to what Mrs. Bayles did with the pie. If students can see and hear evidence that the teacher values all voices equally, not just those that the students have given high status, can truly make a difference in how they start placing their status beliefs.

What I saw change in the class slowly, wasn’t the status that the kids all gave Ernie. In fact, if anything he got even more from finding his own error – but what happened was that girl who had spoken under her breath, spoke a little more loudly. Students who presumed that Ernie was correct, asked an interesting question that Ernie had to justify. These other students were growing in the status that the others were giving them. I believe that it is very hard for us as teachers to control what the students come into the classroom believing about each other, but we can have an impact on what they believe is valuable and meaningful about what they do in the classroom.