It’s 1976 and I’m in Mrs. Gerber’s second grade classroom. After learning our times tables by heart (I was so proud), I’m sitting at my four-table group and Mrs. Gerber comes over handing out something small and square with buttons that looks really cool. She introduces us to the four-function calculator and while lots of other students are seeing what they can write with numbers upside down on the small screen, I am plugging in the biggest numbers I can think of and seeing what the product would be. When will it be too big for the screen? What will it tell me? Is there a pattern in the numbers?

I was able to come up with some questions that Mrs. Gerber hadn’t even thought of, and it was all because of this new toy that I was able to play with in class. Times have definitely changed since then and the “toys” that students play with in class currently, were probably unimaginable in 1976. However, one thing still rings true: that playing with those toys changes everything.

As a math teacher since 1990, I have seen many phases of technological change in education. I remember learning how to use the TI-83 calculator for the first time and thinking of the wonderful ways that this would change the way I taught. So many questions existed about what was important and what was not to change or retain in the curriculum.

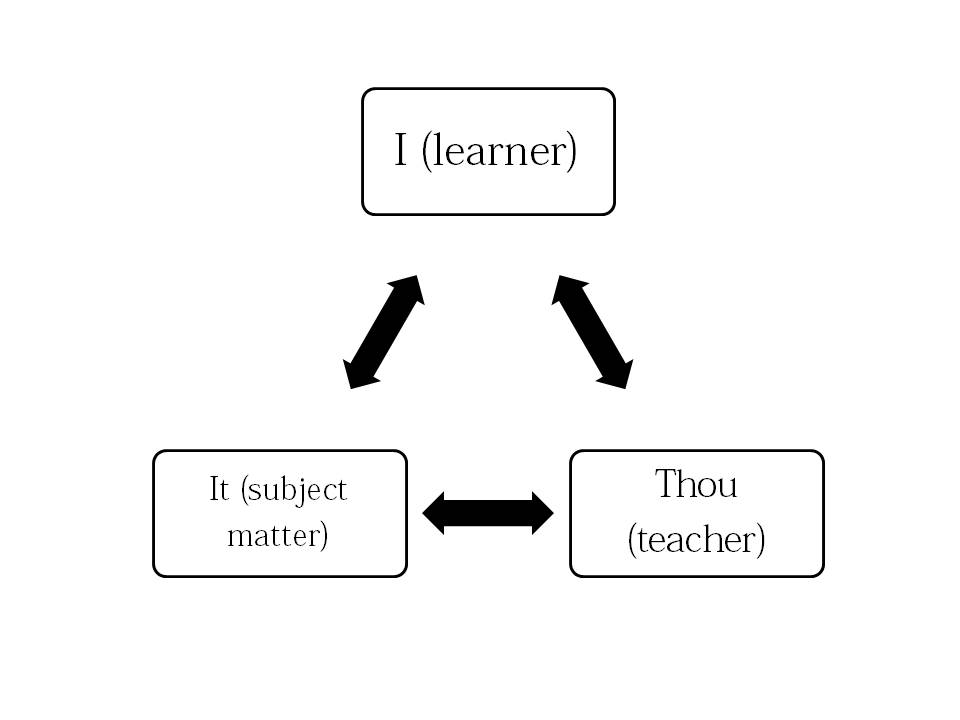

We are once again at a crossroads – one that math education has seen a number of times – where we as a group (or often individuals) decide the importance of specific topics that are “covered” in our curriculum. This autonomy given to math teachers often varies from district to district, even school to school – especially in the independent school world. The eternal question that math teachers do not have enough time to “cover” the contents of the textbook has now come to another moment – What can we leave out and still call ourselves math teachers? Still call our learning outcomes mathematics? The advent of AI should make us all think about what we as mathematicians and educators, think teaching math should be about. AI can serve as tutor, assessor, colleague, student peer and many other roles. What is it we’d want to get out of that “relationship” with the AI?

Personally, I have been contemplating this for a long time and I still come back to the curriculum. There’s so much at this point in education that is extremely intertwined and hard to untangle:

• Working with digital natives for whom technology may not be the best of devices to be interacting with

• The risk-taking and being wrong that students today are mostly lacking

• College admissions dependency on an age-old tradition of racing to Calculus

• The phenomenon of the ‘snowplow’ parent who seeks to remove all obstacles and suffering from a student’ pathway

All these issues affect the way we look at curriculum for mathematics education. Many say that too much access to technology undoes all the skills that may have laid the foundation of students’ mathematical understanding. Others say that students will use the technology as a crutch and not truly “learn” the skills they need or learn from their own mistakes. Teachers will cite the necessity for certain traditional skills based on students’ need to be able to take Calculus by grade 12. Parents will create the obligation of the school to allow students to use AI for homework since the expectations of the school or teacher are “too high.”

It is always important at these crossroads to consider the skills that students learn through the curriculum. What are our goals for teaching factoring? Finding horizontal asymptotes for rational functions? Simplifying complex rational expressions by hand? Memorizing SOHCAHTOA? Why do we teach these skills? If the purpose or answer is so that students can do math “in their head” or “on their own”, my response to this is that eventually this will no longer be required. What we’ve wanted as math teachers as far back as 1990 (and probably further) and what mathematics researchers like Carpenter, Fennema and Schoenfeld have been promoting is “teaching for understanding” or “making sense” of mathematics.

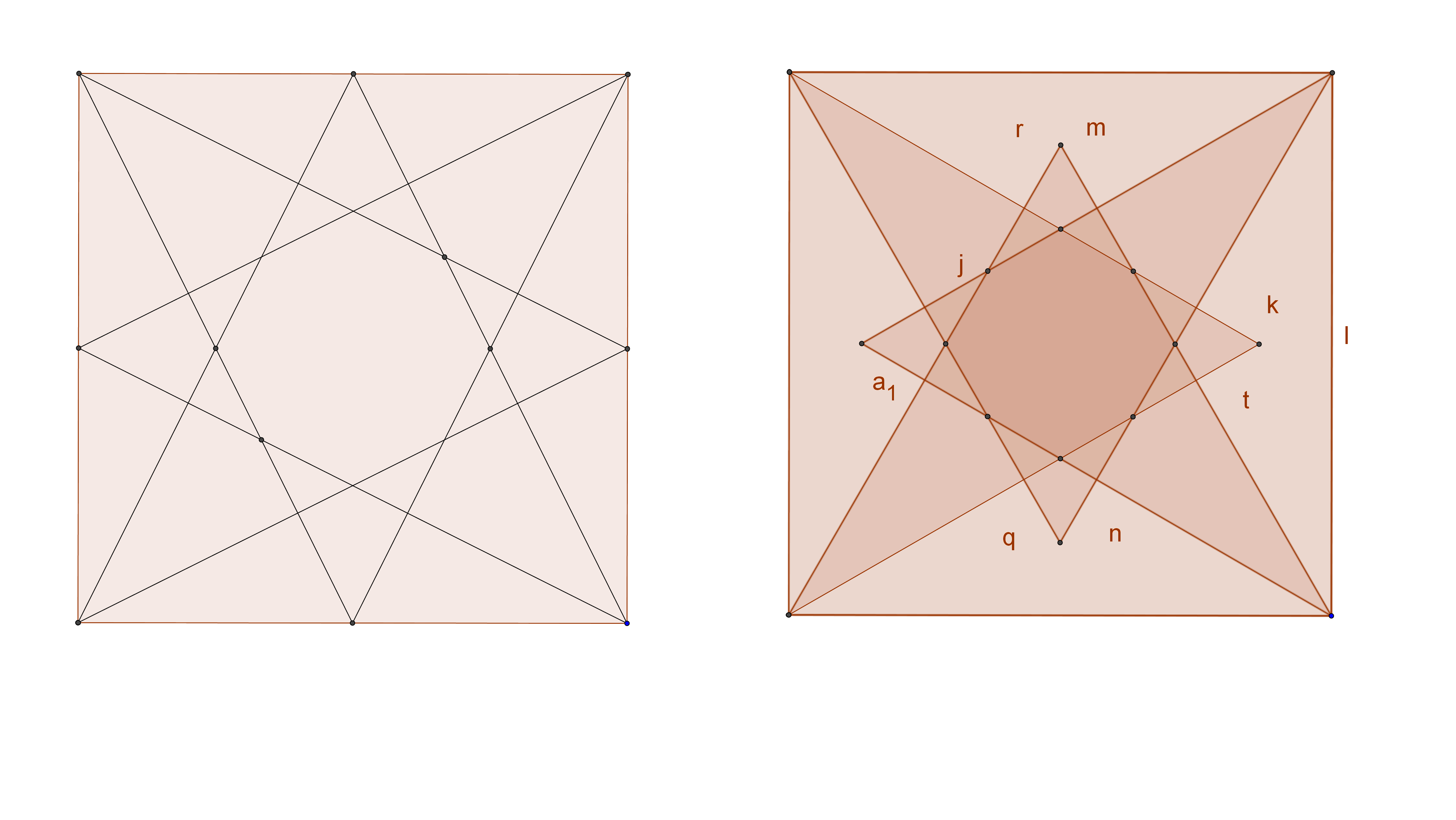

We as a community need to grapple with the question of what is most important to understand and how what we as humans are capable of will be more than what an AI can “understand” for us. Creating a holistic view of teaching mathematics means to dive into the new world of AI and look at the understanding and skills students see as “mathematics” while at the same time considering the new possibilities of what math can be. Instead of factoring, solving, using, “plugging in”, perhaps we change the curriculum so that inquiring, critiquing, deciding and evaluating are the ideas that come to mind when students think of math with AI? Could empathy, discussion, collaboration and abstraction be the main learning outcomes of mathematics education since so much can be done with AI now?

Contemplating these possible futures takes courage, knowledge and experience. I am sure that as a community, we will eventually get there. We will continue to have students that will want to write “hello” upside-down on their calculator (or other words!), but we will also have that students that push the AI to see what they are capable of. We can change what we teach in the mathematics classroom to encourage all students to experiment with curiosity and to help us shape the future.