I just read a great blogpost by a business writer, Gwen Moran, entitled, “SIx Habits of Resilient People.” When I think of people that I admire in my life for their resilience there was usually some circumstance in their life that led them to learn the quality of resilience because they had to. Even the examples that the author uses in this blogpost – being diagnosed with breast cancer, almost being murdered by a mugger, the inability to find a job – these tragedies that people have had to deal with can be turned into positive experiences by seeing them as ways in which we can learn and grow and find strength within ourselves.

But wouldn’t it be great if it didn’t take a negative experience like that to teach us how to be resilient? What if the small things that we did every day slowly taught us resilience instead of one huge experience that we had no choice but to face? Having to deal with small, undesirable circumstances on a daily basis, with the help and support of a caring learning community would be much more preferable, in my opinion, than surviving a mugging. (Not that one is more valuable than the other). But I just wonder – and I’m truly ruminating here, I have no idea – if it is possible to simulate the same type of learning experience on a slower, deeper scale by asking students to learn in a way that they might not like, that might make them uncomfortable, that asks more of them, on a regular basis.

I think you know what I’m getting at. Does PBL actually teach resilience (while also teaching so much more)? In my experience teaching with PBL the feedback I’ve received from students has been overwhelmingly positive in the end. But initially the comments are like this:

“This is so much harder.”

“Why don’t you just tell us what we need to know.”

“I need more practice of the same problems.”

“This type of learning just doesn’t work for me.”

Having students face learning in an uncomfortable atmosphere and face what is hard and unknown is difficult. Thinking for themselves and working together to find answers to problems that they pose as well as their peers pose is very different and unfamiliar. But does it teach the habits that Gwen Moran claim create resilient people? Let’s see. She claims that resilient people….

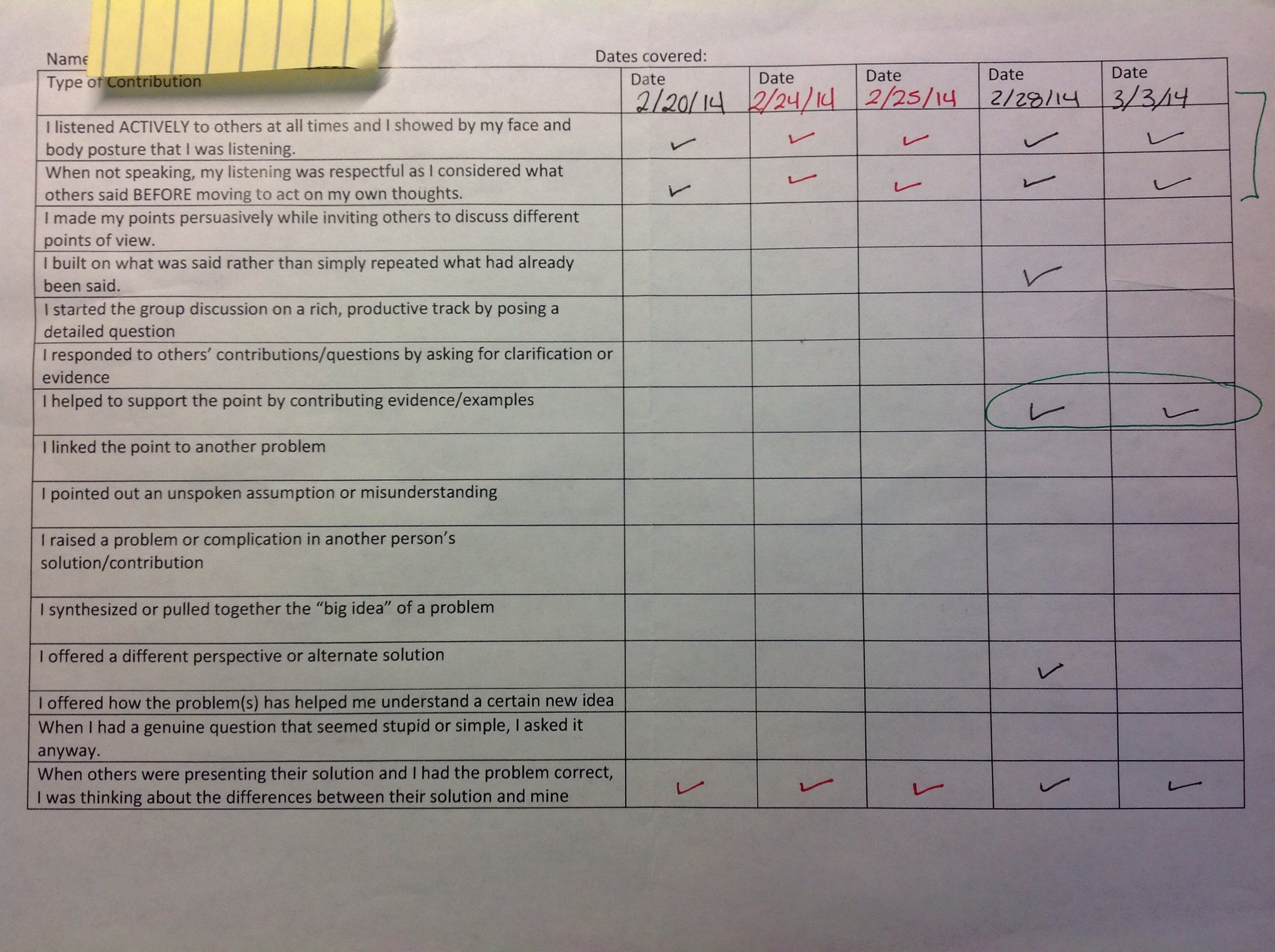

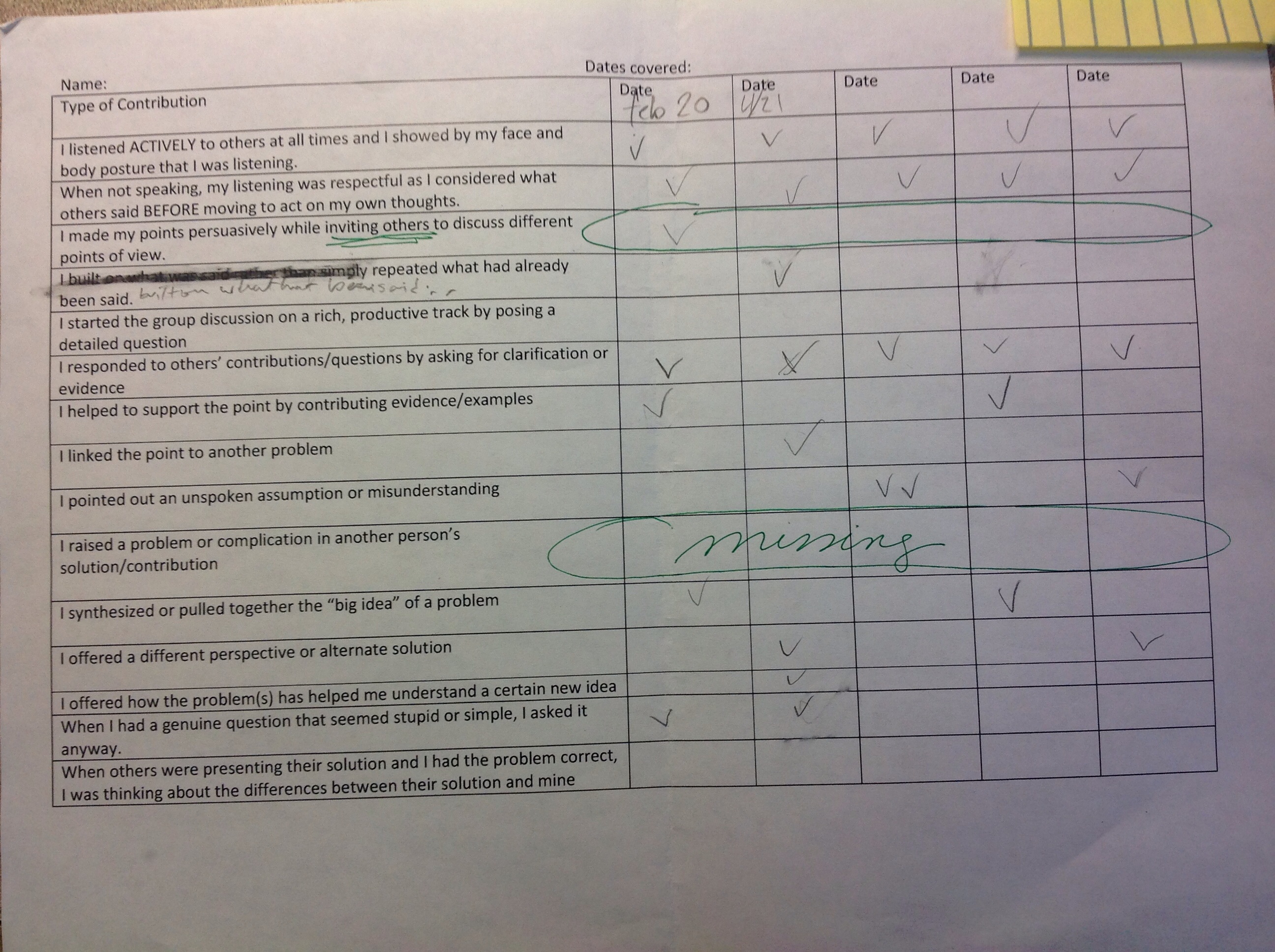

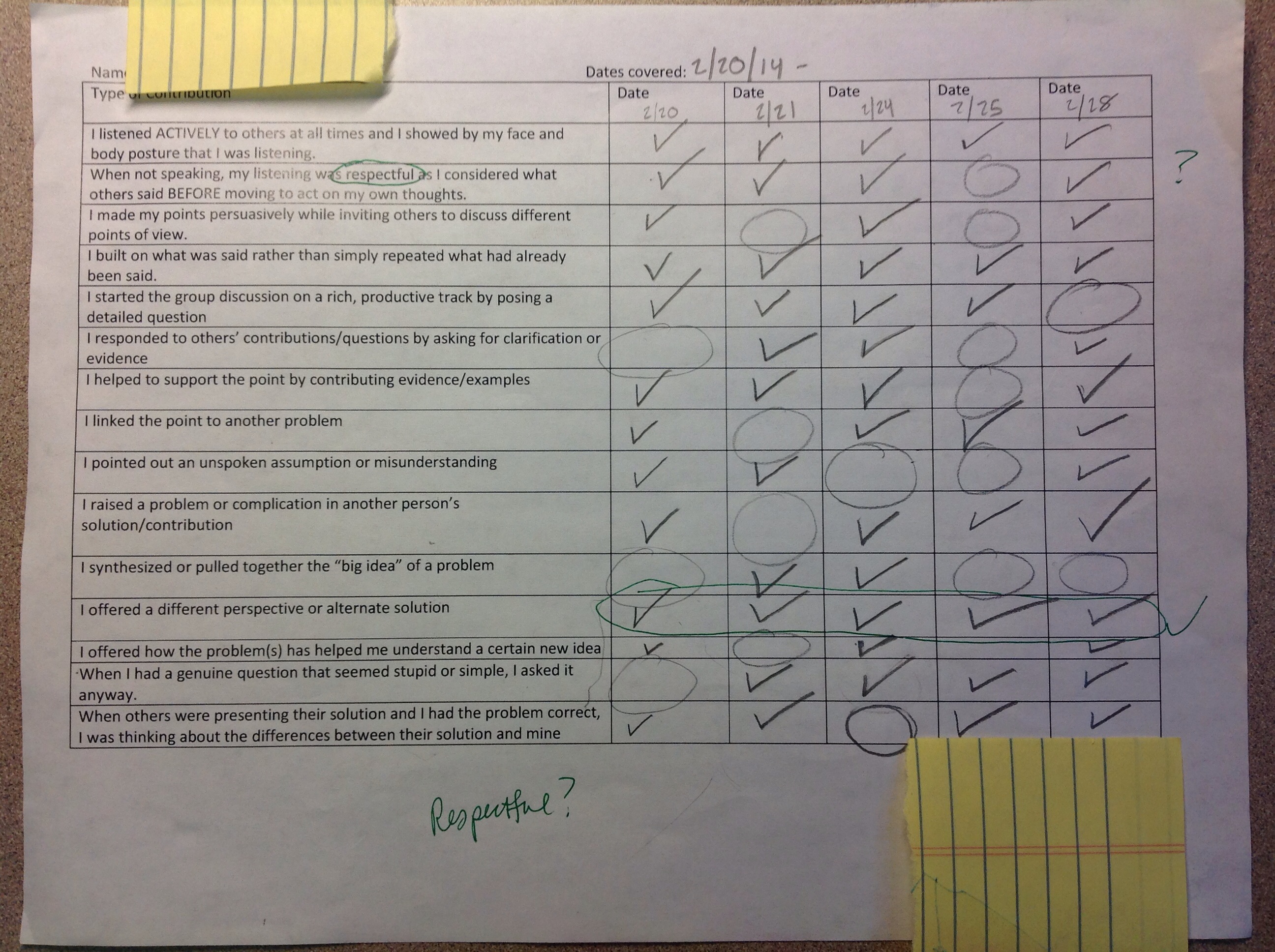

1.Build relationships – I think I can speak to this one with some expertise and say that at least if the PBL classroom is run with a relational pedagogy then it is very true that PBL teaches to build relationship. My dissertation research concluded nothing less. In discussing and sharing your ideas, it is almost impossible not to – you need relational trust and authority in order to share your knowledge with your classmates and teacher and this will only grow the more the system works for each student.

2. Reframe past hurts. – If we assume that real-life “hurts” are analogous to classroom mistakes, then I would say most definitely. PBL teaches you to reframe your mistakes. PBL is a constant cycle of attempting a problem->observing the flaw in your solution ->trying something else and starting all over again. This process of “reframing” the original method is the means by which students learn the the PBL classroom.

3. Accept failure – This may be the #1 thing that PBL teaches. I am constantly telling my students about how great it is to be wrong and make mistakes. You cannot have success without failing in this class. In fact, it is an essential part of learning. However, students in the US have been conditioned not to fail, so that reconditioning takes a very long time and is a difficult process.

4. Have multiple identities – In a traditional classroom, certain students fulfill certain roles – there’s the class clown, the teacher’s pet, the “Hermione Grainger” who is constantly answering the teacher’s questions, etc. But what I’ve found happens in the PBL classroom is that even the student who finds him/herself always answering questions, will also find him/herself learning something from the person s/he thought didn’t know anything the next day. Those roles get broken down because the authority that once belonged only to certain people in the room has been dissolved and the assumption is that all voices have authority. All ideas are heard and discussed. PBL definitely teaches a student to have multiple identities while also teaching them a lot about themselves, and possibly humility, if done right.

5. Practice forgiveness – This might take some reinterpreting in terms of learning, but I do believe there are lessons of forgiveness in the PBL classroom. Students who expect themselves to learn everything the first time and when they don’t, feel stupid, need to forgive themselves and realize that learning is an ongoing process. Learning takes time and maybe needs more than one experience with a topic to see what the deeper meanings and understandings really are. Since PBL is not just a repetitive, rote teaching method, students need to learn how to be patient and forgiving of their own weaknesses as a learner and take time to see themselves as big picture learners.

6. Have a sense of purpose – This habit is about “big picture” purpose and looking at a plan. From the research that I did, I also found that PBL brings together many topics in mathematics, allowing students to see the “big picture” connections between topics much better than traditional teaching does. The decompartmentalization that occurs (as opposed to compartmentalizing topics into chapters in a textbook) is confusing at first because they are not used to it, but eventually students see how topics thread together. Just the other day in my geometry class we were doing a problem where they were asking to find as many points as possible that were 3 units away from (5,4) on the coordinate plane. A student in the class asked, “is this how we are going to get into circles?” The whole class was like “Oh my gosh, it is, isn’t it?” Bam, sense of purpose.

All in all, I feel that PBL meets Moran’s criteria of “resilience characteristics” in ways in which it allows students to practice these habits on a regular basis. So not only does PBL help students learn collaboration, communication and creativity, but perhaps they will see the benefits over time in learning how to move forward from a setback – just a little.