“A self-compassionate attitude could help us feel comforted when we witness the fallibility of other humans.”

Newman, 9/4/19 Greater Good Magazine

This is the conclusion of a research study that was done by researchers at the University of Waterloo, when they asked 100 recruited students to record a video about themselves to be rated on a scale from 1-9 on how “great” they were (see study for more details).

Unbeknowst to them, there were no objective observers, the study actually began when students were shown peers’ scores sometimes mediocre and sometimes outstanding. The question really was “how do you react when you have a sense of failure in the face of others’ success?” Of course, the findings were interesting. It depended on the person. If they were the type of person that had a great sense of how life is wrought with failure and learning from our mistakes, they were more likely to have an adaptable, compassionate, and sympathetic reaction to others’ failure. However, if the student had the habit of being hard on themselves for failing, that is often what they reflected onto others and had a hard time being sympathetic.

As I read this research study, I could not help but put all of this into the context of the PBL classroom. I immediately thought “this is why whole-class discussion with sharing authority is so important.” In order for the failure of the presenter to be shared by the class and experienced as the shared experienced of failure, students should hear ideas, discuss the pros and cons and loopholes and catch the mistakes together. This could not have happened in isolation or in pairs (caveat: not to say that whole class discussion is the only way it can happen or is the only PBL should happen). The shared experience of confusion, being sympathetic to the confusion, the risk-taking of embarassment or being wrong, needs to happen for everyone to say “I know what that feels like.”

Of course, this needs to be done a classroom that fosters the idea that this is a good thing – we need to make mistakes and learn from them – in a safe, non-hierarchical environment where status and positioning are being closely reflected upon by the teacher. What this study shows is that the other mindset (e.g. fixed, as we’ve come to call it) won’t necessarily embrace the shared failure and could make the shared failure counterproductive. This is a hugely important part of the dynamics of a PBL classroom.

I can’t help but recall a student that I interviewed for my dissertation research and how she captured her feeling about shared failure, in that by contributing ideas, the failures or mistakes become a shared success:

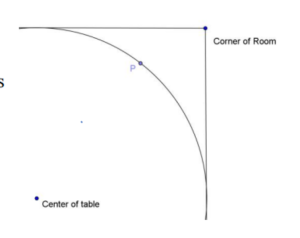

You could kind of add in your own perspective, and kind of give you this sense like, “Ooooh, I helped with this problem” and then another person comes in and they helped with the problem, and by the end, no one knows who solved the problem. Like, everyone contributed their ideas to this problem and you can look at this problem on the board and you can maybe only see one person’s handwriting, but behind their handwriting is everyone’s ideas. So yeah, it’s a sense of “our problem.” It’s not just Karen’s problem, it’s not just whoever’s problem, it’s “our problem.”

Kaley, Schettino Dissertation 2013