Yes, it is this time of year where I have to stop and wonder – what the heck am I doing wrong? Is it me? Is it the kids? Is it the combination of us? In the spring, many of the kids are breezing through and finding ways to problem solve and have gotten really comfortable with being uncomfortable in doing their nightly struggle – they’ve learned to trust that when we get together the next day, their questions will get answered and all will come together, if not that day, then the next.

This year is somewhat more frustrating for me and I can’t figure out why. I feel as if the students are still attempting to get everything right every night. It’s as if they created habits that I did not see somewhere along the way. Reading the beginning of Andrew Gael’s blogpost on Productive Struggle made me realize this was true and I’m more frustrated than ever now. I’ve noticed that the conversations that I am “facilitating” are actually either one student talking about their ideas (basically the kid who thought they got it right) and everyone listening intently checking if they agree with him/her or everyone remaining silent until the one or two kids who are willing to take the risk speak up and take the risk to see if they are right. I’m not quite sure what this is about.

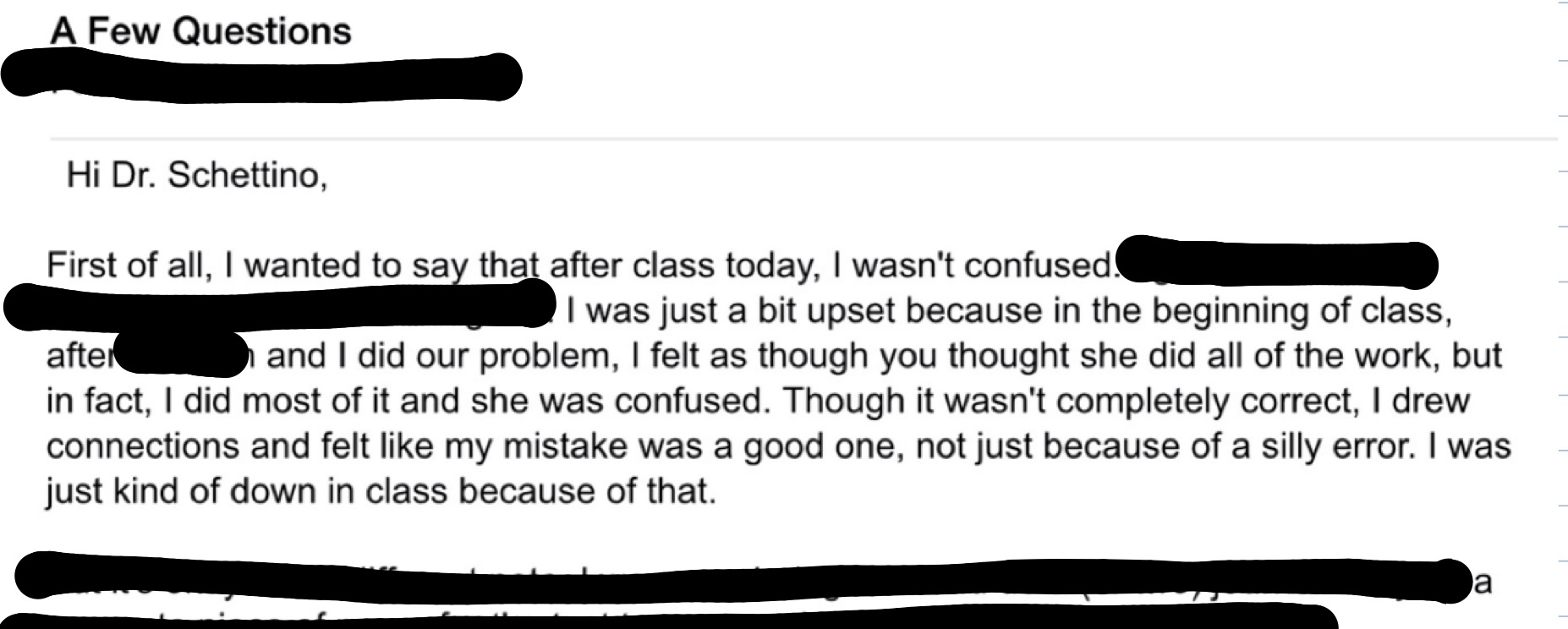

In prior years, there have been kids that really felt much more comfortable with attempting something and being wrong. I am really wondering what I did differently this year. There is much more of a feeling of holding back – many more caveats of “I don’t think this is right…” before someone puts their ideas on the board (even though I repeatedly stress that that is not important.)

I have in the past few years become very disillusioned with the idea that high school students are capable of undoing 12-14 years of fixed mindset. I think I tweeted about this last year sometime when, after a conversation and exercise about Fixed vs. Growth Mindset a student said to me “Is this supposed to make us feel bad?” I was in shock. I couldn’t figure out what I had done to make him feel bad at all as I had done just what Carol Dweck suggests and presented the two mindsets as a continuum – a journey of learning about yourself and how you learn best. Some of the kids saw it as a good tool to know about yourself, but many of them saw it as just one more thing they had to “overcome” in order to get in to a good college or to be the “best they can be” – because you know, if you have a fixed mindset, that’s not the “best you can be” – you have to change that too now. Oh god, what have I done?

So, maybe there’s a little part of me that feels bad for them and truly understands the fear of being wrong. My goals are to prepare them for the thinking, for problem solving in life and their immediate goals are getting good grades, doing the best they can right now to get into a good college, etc. Sometimes these goals are definitely at odds and it’s really tough to compete with the immediacy of what they perceive as success for them and those people they want so much to make proud. And as always when there are two parties who have goals that are at odds – there is ultimately conflict. And the battle continues.