Happy New Year! It’s been a busy end of 2013 for me. I’ve been doing a lot of reading and catching up with some writing. So, the New York Times came out with their top 75 Best-Selling Education Books of 2013 and some of them are really great reads and some are just books that are commercially hyped education jargon. I’ll let you read it for yourself and see which you think are which. But this inspired me to think about what I would recommend as great reading for PBL teachers in terms of mathematics. It’s not always easy to get inspired to continue with PBL so I am always on the look-out for good reads and things that might help me to find ways to motivate students in the classroom. I also hate those lists from articles that seem to have all the answers but then when you read them nothing is ever really black and white like “To Flip or Not to Flip: that is the Question” or “5 Resolutions to Modernize Your Teaching For 2014” or “Top 100 Tools for Learning in 2014” – geez, does anyone just write about one thing anymore? Or even give critical analysis of why these are the reasons to flip, or an argument as to the top 100 tools – anyone can make a list.

Including me! So here goes nothing – well, I mean something. I tried to put together some good reading that emphasizes the skills that are needed for working with students in a problem-based classroom. One of the things I hear most from teachers is not necessarily how to work with the curriculum, but how to get students working with each other and how to foster the type of classroom community (curiosity, openness and risk-taking) that is needed in order for students to want to be engaged.

5. The Mistake Manifesto: How Making Mistakes Can Make Us Better by Alina Tugend, 2011.

I first came across Tugend’s writing when I read her Op-Ed piece in the NY Times while ago, but this essay on making mistakes says so much about Tugend’s great attitude towards how mistakes are not only helpful, but are a wiser and more powerful way of learning. She says that “we do single-loop learning when we need to do double-loop learning.” I love that and I believe that PBL’s method of returning to ideas in its scaffolded and multi-topic approach often allows students to revisit ideas multiple times. Tugend talks about how most of our society creates a fear of making mistakes because we have this idea that we aren’t supposed to make mistakes. This is in turn makes us all risk-averse unfortunately and only allows the most unstructured students and learners to be creative innovators. This is what we have to turn around. Her manifesto doesn’t necessarily tell us how to do this, but it’s a wonderful argument for why we should.

4. Flow, by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, 1990

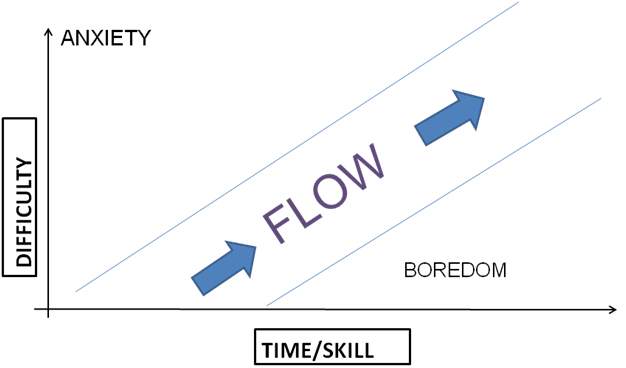

This book’s original intent was to investigate the psychological experience of happiness, however this past year it became connected for me to the process of problem-based learning. OK, so this book is not from 2013 – or even from the past few years, but what happened in 2013, is that I read an article that sent me to this book. The article was called “The Problem-Based Learning Process as finding and being in Flow” by Terry Barrett and it discussed the concept of ‘flow’ (from Csikszentmihalyi’s book) and compared the PBL process (the discourse that occurs, the exchange of ideas and that learning process itself) to the optimization of creativity that occurs in the ‘flow’ process. In this book, Csikszentmihalyi defines ‘flow’ as “the state in which people are so involved in an activity that nothing else seems to matter. The experience itself is so enjoyable that people will do it even at great cost, for the sheer sake of doing it.”(Csikszentmihalyi, p.4). Wouldn’t that be great if that’s the way students viewed learning? One way to see it is like this:

(Barrett, 2013)

The idea being that the state of flow in learning comes when the optimal problem or activity is presented to students such that the difficulty and time or skills given keeps their interest long enough to minimize anxiety and maximize love of learning and the return on their learning (reinforcement of confidence, efficacy, enjoyment, agency, etc.). A lot of the book is based on the idea of the state of flow helping to create the optimal state of happiness so it might not relate directly to teaching, but I highly recommend the last two chapters which are entitled “Creating Chaos” and “The Making of Meaning” which can be directly translated to the PBL classroom and are highly useful for the PBL teacher looking to see how you can create the state of flow for your students.

Tomorrow I will catch up with numbers two and three! (hopefully get you #1 as well)